By Nandani Azad

Women and cooperation play a significant role in the Indian economy especially as no other country in the world has a co-operative movement as large and as diverse as India. Even prior to the current day cooperatives, the concept of cooperation & its activities prevailed in several parts of India known differently i.e., Devarai or Vanarai, Chit funds, Kuries, Bhishis, Phads (some of these were utilized by women solely). The co-operative movement can be defined as a “Voluntary movement of the people carried out democratically by pooling together their resources on the given activity, with the purpose of achieving certain benefits or advantage, which are given to people that cannot get it individually and with the purpose of promoting certain virtue and values such as self help, mutual help, self reliance and general goods of all.” Infact the leaders of the India’s independence saw the cooperative movement as an important tool in carrying forward the policy of rapid and equitable economic development, becoming a part of the National Five year Development Plan efforts. The Self-Help Group model of development a type of cooperation, mostly common amongst poor women is a 20th century social innovation is a micro level privatization of the financial inclusion cooperative model. Cooperatives find explicit mention in two places in the Indian Constitution. First, as part of Article 43 as a Directive Principle which enjoins the State to promote cottage industry through individual or cooperative basis in rural areas and second, in schedule 7 as entries 43 and 44 in the Union list and as entry 32 in the State list.

The first Co-operative Credit Societies Act, came into force in 1904 and a historic milestone in the co-operative movement of India – a turning point in economic and social history. This Act aimed at encouraging thrift habits among the poor peasants and artisans by setting up co-operative societies, that were to counter the role of the exploitative moneylenders. In 1912 the original act was replaced by the Co-operative Societies Act, India aiming at societies dealing not only with credit, but also with insurance and various specialized functions. Today, the co-operative movement in India is the largest in the world with more than 0.6 million individual cooperatives catering to over 240 million members. The movement has permeated all walks and sectors of life, i.e., agriculture, horticulture,credit and banking, housing, agro-industries, sugar, rural electrification, irrigation, water harvesting, labour, weaker sections, dairy, consumers, public distribution system, international trade, exports, agri-business, human resource development, information technology, etc. The cooperative sector generates self-employment to 17.80 million people and has a membership of around 1 million women in 3740 women’s cooperatives. The cooperative movement has now covered 100 per cent of villages in India

along with 65 percent of households bringing rapid transformation both in social, political and economic arena ensuring growth with equity and inclusiveness.

India’s commitment to women reaffirmed by National & International covenants

The following are India’s commitments to the National & International covenants:

- UN Sustainable Development Goals – 2015 (SDGs) – Gender equality fundamental for global growth and poverty reduction.

- CEDAW (The UN Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women).

- The Beijing Plan of Action

- The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).

- The International Labour Organisation (ILO) Recommendation N0.193 (7.3) – increasing women’s participation at all levels in cooperatives.

- National policy on Women’s Empowerment (past and currently being drafted by Ministry of Women and Child Development, Government of India.)

The Role and Importance of Gender Disaggregated Data in Cooperatives

Gender inequity results from a set of attitudes, beliefs and practices – barriers to gender equality. The position and condition of women require analysis within a gender perspective to understand the issues that need to be addressed. But beliefs about gender often cannot be challenged because of the lack of data – in this instance gender disaggregated data – a vital monitoring and program planning tool for identifying the bottlenecks, challenges to women’s participation. The most common reasons cited for not collecting disaggregated data are: lack of staff; lack of resources; lack of skills/expertise; other reasons include eliciting women-related information due to cultural barriers. However, it is indeed a reflection of the low priority given to this vital tool globally for increasing the participation of the poor, women and or co-operatives.

Gender Disaggregated Data: Status of Women in Cooperatives

A recent pioneering study on gender disaggregated data: study of the Status of Women in Cooperatives in the Asia-Pacific was well received at the 10th Asia Pacific Cooperative Ministers’ Conference (APCMC) held in Vietnam in April 2017 (ICA-AP). It led to a historic milestone since the APCMC accepted 33% ratio in women’s participation at all levels of cooperatives in the Asia and Pacific region for the first time. This pioneering study entitled ‘Gender is more than Statistic’ was undertaken to assess the gender quotient in co-operatives in the Asia Pacific region highlighted interesting data, facts and case studies (Azad 2016). It’s salient finding was that women’s representation in co-operatives at higher echelons is not significant at decision making levels through new trends, decisions, issues indicate new threshold of change for women. Nineteen out of 26 countries in Asia Pacific represented in the study (Japan, China, India etc.,) revealed that while the ratio of women chairpersons increased from 7 percent in 2005 to 10 per cent in 2016, the number of women leaders at the top remained abysmally low. However, the ratio of women vice chairpersons increased from 18 percent to 23 percent in 2005 and 2016 respectively. Lack of women’s representation at the top could be attributed to patriarchal values and lack of education and skills that restricted access to leadership positions. Sectors represented were Agriculture, consumer, credit and savings, fishery, fertilizers, finance and banking, land, service related sectors. Both quantitative and qualitative methods were utilized for data collection as well as best practices/individual cases. (Azad, 2016).

Salient Findings

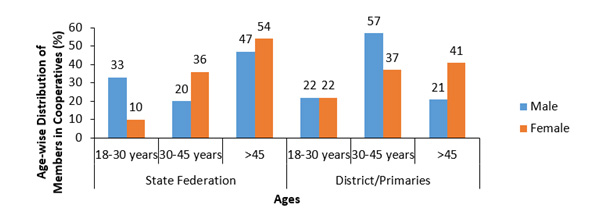

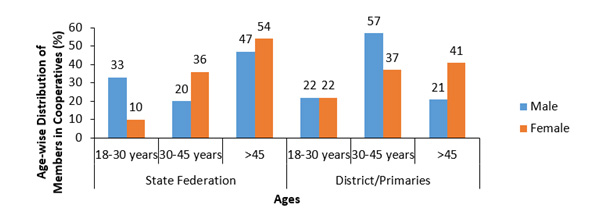

The average male to female ratio membership in cooperatives was 74:26 even at the primary levels in the mixed cooperatives. Majority of women members above 45 years of age and male members of productive age (18-45 years). Twin burdens of women, i.e. reproduction as well as production could be reason for age disparity of male and female members.

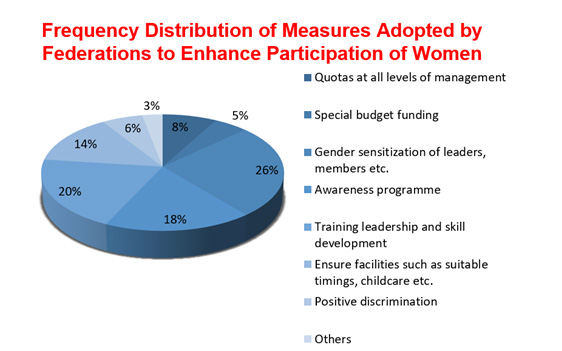

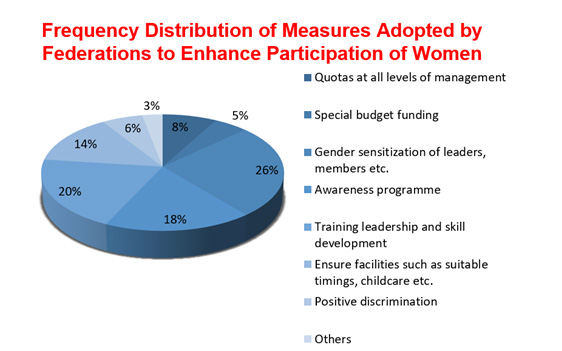

Frequency Distribution of Measures Adopted by Corporative Apex Federations to Enhance Participation of Women

Bottlenecks and Challenges identified by the Apex Respondents

The response to the section on bottlenecks and challenges was quite relevant with respect to the insights into women’s participation in cooperatives. The major obstacles to women’s participation cited were:

- Limited access to education, technical skill, training, etc.

- Socio-economic norms and domestic responsibility stereotype emerge as another major challenge.

- Other impediments raised were lack of emphasis on women’s participation perse, lack of provisions in the bye-laws of cooperatives, cultural barriers, patriarchy, lack of confidence, etc.

- Some challenges for women’s participation were lack of national organisations, full time staff, project funding, low emphasis on women’s participation in development, motivating women to participate in decision making, breaking social by orthodox stereotypes and to compete with men for managerial positions in male dominated offices.

- Women were also not able to seize opportunities provided by cooperative structures due to their lack of access to certain types of resources, i.e production inputs, credit, land or educational level often much less than men or awareness of cooperative structures and their activities.

- Often business experience is very limited for women and does not provide the background to participate in cooperatives;

- Often excluded by support structures that provide marketing technology and other productive resources.

- In un-served areas, business viable business positions, were not accessible to women workers (due to lack of assets, land or collateral) as they had little negotiating power being viewed as a “credit risk”.

- High interest rates per month reduce their margins, profitability and erodes into their savings when their loan approval becomes a reality.

- In several developing countries, savings and credit cooperatives receive support from the government. Though this is widespread, they have still not been able to enhance membership of women.

Overall Study Recommendations

- Sensitize cooperative leaders to grasp the complexity of women’s issues .

- Mainstream gender analysis in all aspects of cooperatives

- Establish “gender equality committees” or cells/units to identify gender-related problems, develop gender awareness trainings and capacity building.

- Increase the membership of women and youth in co-operatives particularly on the board.

- National census/organizations/networks to support in collecting gender disaggregated data

- Partner with cooperatives for actualizing UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

- Track equality indicators such as women’s participation in governance, management membership, asset ownership and income parity on an on going basis to ensure accountability

- Support cooperatives to face challenges of the open market economy, globalization, and technological change.

- Recognize cooperatives as a legitimate form of business (e.g. include the cooperative model in educational curricula and entrepreneurship training programs).

Women & Cooperatives

Cooperatives being driven by women are often an ideal model and most suitable to be practiced. Development has to achieve what women themselves perceive to be of their interest. In the process people’s empowerment and enrichment, cooperatives enable women to realize their potential, build self- confidence and lead lives of dignity and fulfilment are attained. It has been proved that cooperatives are the effective’s tool to attain collective goal, women come together for a common cause to raise and manage resource for the benefit of the lives-both economically, socially and for the welfare of their family.

It has also been found that through cooperatives in urban and rural areas, women have been empowered by the correct support with the right support system; they too have shown that theycan lead and contribute positively to the well – being of the society. Women’s empowerment through cooperatives show the collective well being of the women. However, only if they are respected well in the decision making process in the five progressive levels of equality through cooperatives denoting a higher level of empowerment in areas of social or economic life.

Progressive levels of Equality through Cooperatives

Participation Women have equal participation in decision making in all programs and policies

Conscientization Women believe the gender roles can be changed and gender equality is possible

Control Women and men have equal control over factors of production and distribution of benefits, without dominance or subordination

Access Women gain access to resources such as land, labor, credit, training, marketing facilities, public services and benefit on an equal basis with men. Reforms of law and practice may be prerequisites for such access

Welfare Women’s material needs such as food, income and medical care are met

Forms of Women’s Empowerment through cooperatives

Economic empowerment: Cooperatives facilitate economic empowerment through access to economic resources and opportunities including jobs, financial services such as credit, productive assets, development skills and market information. Due to economic empowerment women participate, contribute and benefit from development processes which recognizes their contribution, respect their dignity and make it possible to negotiate a fair distribution of the benefits of development.

Increased well-being: Economic empowered women contribute to the well-being of their families and their husband and are in position to raise income through entrepreneurship. An increase in income is utilized towards improving the family wellbeing.

Social and political empowerment: As a consequence of economic empowerment women increase confidence and are be in a position to raise their voices, make choices and be able to contribute in social & political matters that affect their daily lives.

Significance of Women’s Co-operative Banks

Women’s co-operative banks have been formed with a social purpose and therefore, it needs special encouragement from the government and the society. The Constitution of Women’s Co-operative Banks provides that all managing committee members of the women’s Cooperative Banks should be women. The President/Chairperson is invariably a woman. The objectives of women’s Co-operative Banks focus on women welfare, emancipation of women and encouragement to women. All borrowers as well as members are women.

In contrast to the mixed cooperatives and participation of women where gender integration is necessary the women’s only cooperatives like the Indian Cooperative Network for Women (ICNW) have demonstrated that in traditional societies this model seems to be more effective in enhancing women’s role in cooperatives. Given below is the case study of the Indian Cooperative Network for women.

Sustainable job creation for Women in the Informal Sector: The case of the

Indian Cooperative Network or Women, Chennai

The large reservoir of poor women in India are in the informal / unorganized sector (90%). Considered a low growth sector, attention on it in terms of investment, protection and regulation, support structures, skill up-gradation, backward and forward linkages are minimal. Unions and bargaining power in this sector are low as there are few formal unions. Conditions of social oppression, poor living conditions, large families, child labour, illiteracy exist.

It is in this environment of powerlessness that the Indian Cooperative Network for Women (ICNW) intervened to help poor women create the foundations of a development model based on altered gender relations, by challenging structural poverty, spearheading social integration, and by transforming labour into capital with the surplus retained for poor women’s needs.

The case of the ICNW is a classic case of countering the pillars of caste / class / gender discrimination as a private player by organizing poor women in this sector (as share holders in credit cooperatives) at nominal interest credit (lowest in the area) through women, by and for women for over 40 years i.e., in the year 1981. Operating at 14 locations in their states of South India, 6,00,769 women members with a 99.87% cumulative repayment. Members are in 267 occupations (trades / productions/ manufacturing / services). Requisite social protection through group delivery savings, training, legal awareness, insurance products are provided. A million loan’s have been disbursed with smallest loan sizes from Rs. 200/- in 1981 to about Rs. 1 Lakh now (i.e. MSME loans) the majority being within the mandatory Rs. 50,000/- classified as micro-loans). Automated software is operated by girls from fisher, coolie and such families in the ICNW credit operations that are regulated under the cooperative structure. The major lesson being that access to timely credit in the understandable terms set by poor women (as clients) through organization and governance devised by them is the prescription for growth, employment, better living standards, out of debt and poverty for women. Constant nurturing, mentoring with multiple products in various steps to enhance their viability as micro-entrepreneurs has contributed to the economic process including accumulation at the base. The concept, programme strategy,

5 year impact survey are highlighted in the next section.

Poor women in the informal sector: Invisibility to visibility

The holistic approach

Gender and equity model

Economic exploitation and social oppression called for a new model of development and intervention based on women’s innate wisdom and response, modelled on existing indigenous collectivities utilizing local modes of communication. The WWF-ICNW facilitated this holistic and equitable intervention model based on ‘women-centred’ development. It also rejected a piecemeal approach to the development and based its services on a holistic perception of gender roles (i.e. women’s roles as economic producers, home managers and community leaders).

The informal sector in South India is akin to those of other countries in terms of conditions of work, but it is entirely different in its cultural setting for poor women, as powerlessness for women is enhanced by the barriers of caste, class and gender. To achieve any results in terms of development, organizations like the WWF/ICNW were required to challenge the five pillars in its manifestation as related to gender. ‘Five interwoven threads of oppression can be discerned: class exploitation caste inferiority, male dominance, isolation in a closed world and physical weakness’. These are explained briefly below.

(1) Class exploitation is visible in the supplier-buyer relationships undergone by members such as lace-makers, agarbathi- makers, beedi workers; it is also discernible in the low wages paid to wage-earners wherein women’s earned surplus accrues else- where; their access to credit is mostly mediated by the money-lender whose exploitation in South Asia is well documented elsewhere.

(2) Caste inferiority restricts women’s mobility and formulates cultural norms for their social behaviour. Lower caste women (the bulk of WWF’s / ICNW membership, i.e., about 85 percent) have often been subject to ‘pollution norms’ whereby upper caste women would not sit, touch, eat, dance or eat with them. These barriers deny access to development resources and information as ‘low caste women are often considered as unworthy of development’.

(3) Patriarchy in the South Asian context is embedded in the values of tradition, customary practices or law and based on culturally determined roles for women restricted to those in and around the household with a view to restricting mobility. Intra-household distribution of less food to women and girl children leads to physical weakness and is compounded by cultural values and superiority of male children. Women are subjected to continuous child birth and poor women continue from birth to death with superstition, dowry, wife-beating and general lack of access to decision-making. Women are often viewed as housewives, marginal or supplementary income providers but not as home managers, economic producers, community leaders or cultural catalysts.

(4) Ill health, numerous children, chronic debilitation, inability to use health services (too distant, too expensive, no time, inaccessible) also make it hard for poor women to break out of their trap. The position is more acute when they are widows left with children (FHH). Many are caught in the sequence of pregnancy and childrearing. On top of all this, many poor working women suffer occupational ailments such as back and joint pains, chronic hand sores, headaches, damage to eyes and so on due to long hours of sitting, hard work of rubbing and rolling and concentration on intricate lacework continued into the night by poor light. (‘We have lost our eyes by doing this”, said many.)

(5) Isolated and in closed walls created by society and poverty, poor women are apathetic, fearful and ignorant of ‘everything to do with the written word’, and this combines to immobilize them in the house, the compound, the street or the village. Children are often pawns in this syndrome which limits their access to schooling or to earning to augment the family income.

The Accumulation Process: The Poor Are Efficient

The sequence

The accumulation process by poor women has taken place at WWF/ICNW in a particular sequence and the process has been replicated in various other socio-economic contexts. It is therefore a viable strategy that has led to a sustained process of development and has cost effectively reached large numbers of poor women within a minimum time. The change from indebtedness and oppression to productive employment and growth, as well as empowerment, has taken place since the first decade of inception. The process can be categorized in three phases.

Phase I

Where all other institutional systems had failed to give poor women access to credit, credit intervention helped them to gradually pay off old debts before they could start to make capital investments.

Phase II

With a lessening of the debt burden and with diversification and growth in enterprises, household food security and quality of physical living were made possible.

Phase III

At the height of this change, once stabilization of businesses occurred, asset creation in the form of education, sanitation, housing and jewellery has taken place, with simultaneous increase in awareness, enhancement of social status, dignity and empowerment. Emerging form the organizational power and collective action is a social platform of 25,000 groups who are making in-roads into the panchayat local government system (ICNW members have been elected to some panchayats), generating demand for government services including the public distribution system, hospitals, schools, or dealing with and challenging civic, municipal and police authorities for solutions and redressing social oppression through creating alternative structures based on women as new leaders in the household and the community.

(Author Nandani Azad is President of ICNW)